I'm so wiped out... I had a 10:00 a.m. appointment with my primary care doctor (about the back pain & feet numbness) and I set the alarm on my phone (which is the alarm I used while away the past week) for 6:30 a.m. The alarm went off and I remember vaguely trying to figure out where the alarm was coming from and turning it off. Then I didn't wake up again until about 10:15! I really wanted to keep that appointment, but there's nothing I can do about it now.

I don't want to say any more about recent happenings right now, so I'm just going to go ahead and return to the Ouchi article. It's been over a week since I discussed it, though, so I may need to warm up a bit.

***

We're still in the "Introduction" section of the article, but now we're in the "4. Designing Control Mechanisms: Costs and Benefits" sub-section.

"On the one hand, there is a cost of search and of acquisition: some skills are rare in the labor force and the organization wanting to hire people with those skills will have to search widely and pay higher wages. Once hired, however, such people will be able to perform their tasks without instruction and, if they have also been selected for values (motivation) they will be inclined to work hard without close supervision, both of which will save the organization money. On the other hand, there is the cost of training the unskilled and the indifferent to learn the organization's skills and values and there is the cost of developing and running a supervisory system to monitor, evaluate, and correct their behavior." (p. 240-241)

Generally, the Vienna mission would have brought on missionaries that were skilled in both the tasks and values the mission thought it needed. Regarding tasks, however, I think it would be assumed that most new workers would not have the tasks specific to working in Eastern Europe and the values might need to be tweaked at least a little to conform to aspects of the mission's operations that weren't public knowledge. I suspect that what the mission would generally hope for in new workers would be professional skills (e.g., secretarial, theological, etc.), proper theological beliefs, and, perhaps, a "healthy fear" of communist regimes and/or conservative political (e.g., Republican, Moral Majority, etc.) beliefs. The mission's socialization tactics were, I think, based on the assumptions that these were all in place before the new missionary arrived in Vienna.

In my case, however, my professional (secretarial) skills were pretty rudimentary, I don't know that I really had any political convictions (i.e., Republican, Democrat) and my "fear" of communist regimes was undoubtedly not as well-developed as the mission would have liked. That is, I hadn't succumbed to the "red scare" mentality, although I didn't agree with communist premises nor like how they had been interpreted and applied in Eastern Europe. The mission, as I've said before, didn't seem terribly concerned that I wasn't a professional secretary, but I don't think it knew that I hadn't met the political requirements, which I didn't know were even relevant. Since I did not have the appropriate political stance I was more prone to question their modus operandi, but there were also other reasons, as I've discussed elsewhere (e.g., my Christian idealism stance), for my not readily adopting their ways. Since the mission was most interested in inculcating "proper" values, which they never succeeded in doing with me, I never really got into serious secretarial work, so my lack in that regard wasn't very important.

In any case, my poor fit in these areas (particularly regarding values) resulted in the mission having to spend a lot of time and money on socializing me, assuming that is what they wanted to do with me.

***

"...[V]arious forms of evaluation and control will result in differing individual levels of commitment to or alienation from the organization and its objectives. In general, a control mode which relies heavily on selecting the appropriate people can expect high commitment as a result of internalized values.

At the other extreme, a control mode which depends heavily upon monitoring, evaluating, and correcting in an explicit manner is likely to offend people's sense of autonomy and of self-control and, as a result, will probably result in an unenthusiastic, purely compliant response. In this state, people require even more close supervision, having been alienated from the organization as a result of its control mechanism." (p. 241.)

This is, in fact, more or less what happened with me, that I developed an "unenthusiastic, purely compliant response," having been alienated from the mission. However, this is over-simplifying what happened to a degree as to distort the mission's actions and my response.

Generally, I think the mission did rely heavily on recruiting the appropriate workers, but knew that in as much as a good chunk of its activities were carried out in secret there would always be at least some work on values adjustment and skill development with new recruits. Generally, however, if the new recruits had a general orientation fitting with the mission's values (and the new member was isolated enough from familiar surroundings and people) it wouldn't be all that difficult to socialize the individual to become fully functioning members of the organization. In this system, however, it wouldn't be very easy for the new worker to de-select him/herself before his/her arrival in Vienna because of all the things s/he didn't know about the mission (because those things were the "secret" aspects of how it functioned). So the onus was on the mission to determine whether or not the individual was a good match in those aspects of the work.

Monitoring and evaluation, as I've said before, was complex but also all-pervasive. That is, one's superiors would be monitoring the newcomer's progress, and I suspect that this was discussed formally and/or informally with other mission leaders. But since everyone was expected to internalize the mission's values and ways of doing things, everyone in the mission could play a monitoring and evaluation role, to one extent or another. This would be were social control came into play. Once one had been fully socialized I suspect that even though these controls were still in place one didn't feel it because one was no on the receiving end of corrective control measures.

In my case, again as I've said before, my "sense of autonomy and self-control" was offended because I didn't think the control measures the mission used were necessary or appropriate for a Christian organization. Also, I didn't think I was doing anything to compromise the mission and also wasn't willing to give up my personal responsibility for making moral judgements, which seemed to be what, at least in part, what was required by the mission. I thought (and still think) such a demand is unbiblical.

So in my case the mission's selection process failed in that by bringing me on they were accepting someone who didn't fit their requirements, and then once there they were (more or less) forced to monitor, evaluate and correct me more than usually was the case.

***

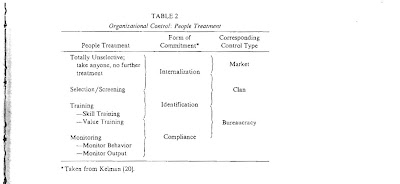

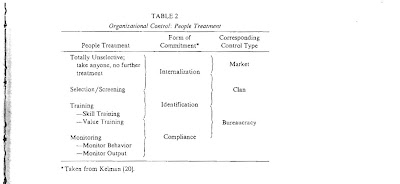

"The link between forms of commitment and types of control is quite direct. Internalized commitment is necessary for a market possesses no hierarchical monitoring or policing capabilities. Internalization is also necessary to a clan, which has weak monitoring abilities, that is, evaluation is subtle and slow under this form of control, and thus, without high commitment, the mechanism is capable of drifting quite far aoff course before being corrected. A clan can also be supported with identification, however, and over time, the identification may be converted into internalization of the values of the clan." (p. 843).

I have to backtrack a little to explain this table (click on it to see it better). The top of the chart would characterize, according to the author, organizations that take anyone "(although we assume that everyone is to some extent self-interested, hedonistic, or profit-maximizing" (p. 841). In these cases, such organizations rely on "commitment of each individual to self, since it employs a market mechanism of control in which what is desired is that each person simply maximize his or her personal well-being (profit). Since the organization's objective is thus identical to the individual's objective, we can say that internalization of objectives exists and thus no close supervision will be necessary, and enthusiasm for persuing the organization's goals will be high (since they are also the individual's selfish goals)." (p. 842)

"Market" does not fit the mission because it was not a profit-making institution. So we would have to substitute "profit-making" for something more along the lines of "ministry" or "indigenous church leadership development" or the like. Indeed, anyone wanting to work with the mission would share these kinds of goals, although they are not strictly a matter of self-interest. But for the mission to use these kinds of control, maybe it would have to turn these into self-interest. In this case, the self-interest of the mission would be for the mission's survival and/or growth and for the individual's career interests. If the individual puts enough stock on the "success" of his/her career and his/her career goals mesh closely enough with those of the mission's, then the basic "market control" set up could be reasonably applied, I think, to the Vienna mission's situation, making these substitutions to account for the mission setting. However, since there were

some controls in place, this would put the mission in the "clan control" category, which fits other things I've said before.

In this scenario, then, the individual needs to have these internalized self-interested career goals in place for successful integration into the mission, although, as the text (in block quotes above) indicates, identification might have sufficed early on in the newcomer's tenure with the mission. In this set up, the mission's controls would mostly be affective early on in the newcomer's tenure with it, while the individual had an identification stance and was being socialized. Once the individual had been socialized and had moved to the internalization stance the mission could remove formal controls, relying solely on social control mechanisms.

It is possible that because evaluation is "subtle and slow" in the clan control context the mission was not able to adequately, correctly, and in a timely fashion identify my "deviance" from their norms and expectations.

So how could they have caught my deviance? I'm not sure I want to answer this question because I don't want to help the mission figure out more inappropriate (read: unbiblical) ways of functioning. Still, answering it might be useful for understanding what happened when I was with the organization. I'm not sure I can answer this question with any certainty, but I can come up with some suggestive possibilities, I think.

One thing was their indirectness, wherein it seemed there were certain "taboo" topics and/or views/opinions/beliefs, etc. This indirectness and tendency to secrecy provided, I think, a cover for me, that I could use just as the mission used it to hide its true identity from outsiders and unsocialized outsiders. I'm not sure I was really conscious of this, except I did learn to keep my mouth shut which I think I knew I extended to include applications the mission intended (e.g., hiding my disagreements with the mission from my boss). If there had been a method for mutual directness, my disagreements would have been more likely to become evident.

Also, if there had been more formal means of evaluation, such as an annual review, in place, it's possible that, if handled correctly, might have resulted in the mission becoming aware of my disagreements with it.

And if the mission had provided more self-fulfilling work for me to do I might not have become alienated, or at least no as much as I was. I had little career-commitment because they didn't give me enough relevant career opportunities for me to think that working with them my career could evolve in a way I wanted it to. As I said above, this individual career-commitment might have been critical for the mission to function well as it did.

There are likely other things the mission could have done to either catch my deviance or avoid me becoming alienated from them.

***

I had to break off here to go to a doctor appointment. I learned that there was some mild throat weakening up near my tongue, but the doctor thinks it's just from the neuro-surgeon having to cut through muscle to do the cervical diskectomy and fusion in January.

While waiting to get in to see the doctor I called a friend who lives sort of near the doctor's office and she came by and we had a nice chat over lunch. She said I even look tired!

I came home and watered my plants and my neighbor came by with another Vitamin Shoppe package. I guess it's the rest of the back order, but I haven't even opened the first box!

I'm having trouble reading with my new computer glasses, which is a real bummer. I guess I should make another appointment with the optometrist.

***

"The social agreement to suspend judgment about orders from superiors and to simply follow orders (see Blau and Scott [7, pp. 29-30]) is fundamental to bureaucratic control." (p. 842)

This could also be said of the Vienna mission, however, the suspension of judgment is more all-encompassing, so that the individual actually comes to share the same mindset that leads to "orders from superiors." So, whereas in bureaucratic control the suspension of judgment is only regarding individual orders, in the Vienna mission it comprises the whole kit and kaboodle - the entirety of the mission enterprise and its activities. I think this fits the clan concept because in a clan control setting individuals adopt the organization's norms.

***

"The issue of commitment and control may also pose a moral question of some significance. If organizations achieve internalized control purely through selection, then, it would seem, both the individual and the organization are unambiguously satisfied. If internalization is achieved through training of employees into the values and beliefs of the organization, however, then it is possible that some individuals may be subject to economic coercion to modify their values. Indeed, this kind of forced socialization is common in certain of our institutions (what Etzioni refers to as "coercive" organizations) such as the U.S. Marine Corps and many mental hospitals. In some such cases, we accept the abrogation of individual's rights as being secondary to a more pressing need. In the case of a company town or a middle-aged employee with few job options, however, we are less likely to approve of this kind of pressure. As long as organizations maintain an essentially democratic power structure, this danger remains remote. If the hierarchy of authority becomes relatively autocratic, however, the possibility of loss of individual freedom becomes real." (p. 842-843).

As an aside, I would like to say that I don't think I'd thought of comparing the Vienna mission to a mental hospital. That is an intriguing thought, however. In any case, I've shown repeatedly how the mission was a total institution and I've discussed the possibility of it being a coercive one also. How coercion is discussed here makes it appear similar to what I experienced in Vienna. That is, similar to the "company town or middle-aged employee..." for those newly arrived in Vienna to work with the mission it would be difficult to leave once one had arrived, and also before one arrived there would be a lot the recruit wouldn't know about (because the mission didn't want to reveal certain things). So the new recruit, faced with demands by the mission to internalize its norms, would have little choice and the effect would be induction by coercion.

Going back to the beginning of this quote, the author indicates that if internalization of organizational demands is achieved through selection than there is mutual agreement upfront, but if this internalization is achieved via training that occurs after recruitment, then there is the possibility of a moral aspect of the internalization process. I'm not sure what normative basis the author is using to come to this conclusion, but in the case of the Vienna mission it appears to me that using the Bible as a basis for moral determination is reasonable, because the mission was a conservative Evangelical Christian organization.

I will just point to my childhood church, named for the church in Berea:

"10As soon as it was night, the brothers sent Paul and Silas away to Berea. On arriving there, they went to the Jewish synagogue. 11Now the Bereans were of more noble character than the Thessalonians, for they received the message with great eagerness and examined the Scriptures every day to see if what Paul said was true. 12Many of the Jews believed, as did also a number of prominent Greek women and many Greek men." (Acts 17: 10-12)

Since the Bereans are extolled for their questioning of Paul and Silas' teaching and searching the Scripture to see if what they were saying was correct, it seems that this kind of thing is good and one that should be encouraged among believers. However, I'm afraid that I can't say that this would be the case in the Vienna mission. That is, first of all, if they found out that someone (e.g., I) was questioning anything they would pull out all stops to put an immediate halt to such deviant behavior. They would, in the process, make sure that it was clear that they had a monopoly on biblical interpretation and everyone was expected to tow that line. And they would undoubtedly find a scriptural basis for stifling any and all such questioning and use of Scripture as an independent basis for finding answer to such questions. I'm not talking about theology here, as they're open about that and everyone would have to have already agreed to their basic creed. I'm talking about questioning of how the organization operated and its reasoning and the like.

The other thing here is that the mission didn't exactly "train" new recruits in the usual sense, except through socialization, which I've discussed already at some length. But there were not h.r. courses in organizational values and norms, for example. I think that a certain amount of the norms were picked up through trial and error as the individual tried to learn the ropes. During that process certain things would be responded to well and others not so well, which helped steer the individual in the right direction, even if not totally consciously. That is, the individual might respond to some of these cues without really understanding that that's what s/he was doing. In a way this would be good for the mission because what wasn't understood consciously would be easier to deny. That is, if the individual didn't understand what s/he had come to internalize, then when faced with a question by someone outside the mission about it s/he could truthfully indicate lack of knowledge or understanding about the question. This kind of thing would than avoid having to be dishonest while serving the same purpose of not divulging organizational secrets.

***

That's all for this sub-section and I'm going to get on with a few other things I have to do.